Sidewalks (Issue #1)

Their past and present and why they matter

Why are sidewalks important to think about?

Like many constants in our lives, sidewalks are not something we often think about. A street element whose main function is to facilitate a pedestrian walking from one place to another, sidewalks have in fact historically been a place of debates on access, use and design. After all, before sidewalks became the strips of road on the side of car traffic we know today, cars and people largely occupied a common street space, where motor vehicles, strollers, bikes, pedestrians and goods all moved together. The story of sidewalks is also the story of what and who gets priority, how design keeps some people out and invites others in and how the choices made about our streets shape our cities and lives.

How did sidewalks come to be? The Case of Jaywalking

To understand the role sidewalks play today, we must consider the history of how they were created and continuously shaped. What were the processes that lead to the modern sidewalk? Who got to decide about it and who was kept out? How did our beliefs and goals play into creating these small building blocks of our city life and what patterns did these processes follow?

Before the invention and popularization of cars, sidewalks were relatively rare. First appearing in Anatolia in 2000 BCE, sidewalks were an occasional presence in urban areas, until they were popularized in Paris in the 1860s. As part of his plans to rebuild the city which was suffering from overcrowding, disease and unrest, Napoleon commissioned the French architect Georges-Eugène Haussmann to spearhead an urban revival movement that aimed at modernizing Paris.

The movement created grand boulevards with wide walkways, lined with streetlights and trees that allowed the city’s street network to connect together. The aim was for Paris to have “light, air, clean water and good sanitation”, moving away from the old narrow streets with non-functional sewer systems to streets connecting the city’s bus stations and already existing boulevards. A major effect of these renovations was the separation of vehicle movement from that of pedestrians, facilitated by the building of extensive sidewalks. This plan was adopted by urban planners across the world’s largest cities like Vienna and in the United States, in Washington. Thus, the sidewalk began its rising popularity across the world.

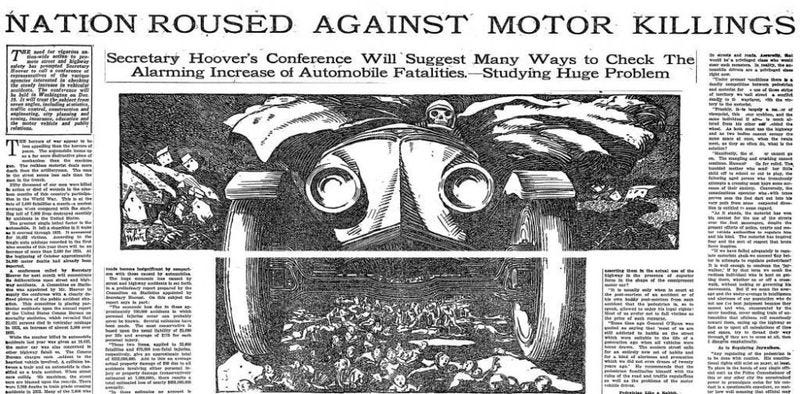

Notably, sidewalks actually preceded the popularization of vehicles. In the period before cars became widely available, sidewalks were intended to protect pedestrians from horse carriages improving the flow of traffic. The role that sidewalks played in street behavior changed with the popularization of cars, especially in the United States. In the US, the increasing number of cars in the street lead to more car-related deaths, and initially the blame was put on the vehicles rather than the people walking. Cars were seen as an intrusion and a break from the normal order of life and deaths from traffic accidents were covered extensively on newspapers. These drivers and their vehicles were villified:

Thus began a debate on the rising dominance of cars in American streets and what that meant for how these vehicles were going to interact with other street users. On the one hand, the public rightfully pointed at the spike in deaths, especially of children and the elderly. They also took action: in 1923 “42,000 Cincinnati residents signed a petition for a ballot initiative that would require all cars to have a governor limiting them to 25 miles per hour”.

On the other hand, the response by car companies was predictably drastic. Automakers and dealerships began a powerful campaign to shift the public’s opinion towards cars by instead assigning blame for accidents to pedestrians. Due to their efforts, local governments eventually released pedestrian controls inhibiting pedestrian movement to sidewalks and crosswalks. The term “jaywalking” was coined to describe crossing the street anywhere but at a crosswalk, and those who did so were subjected to fines. Shame was used as a powerful tool in forcing pedestrians to obey by these laws: police officers whistled at jaywalkers, who were portrayed as dangerous and stupid.

More broadly, the story of jaywalking was part of the answer to the question of “who belongs in a street”. Its rise as a concept sheds light into how our social behaviors get shaped by technology and by those who stand to benefit the most from it. It is also an important example of how the advances in technology are often deemed inevitable and natural, whereas in reality there are many forces shaping human progress; and those that triumph often do so by enforcing their power, rather than because they are offering the best solution.

Design: Good Sidewalks Today

Given this history, what do sidewalks look like today? And what makes a good sidewalk?

While there is no single guide for designing sidewalks across countries, sidewalks should follow a few common principles. According to the World Resources Institute, there are 8 such principles: proper sizing, universal accessibility, safe connections, clear signage, attractive spaces, permanent security, quality surfaces, and efficient drainage:

Source: World Resources Institute Proper Sizing: sidewalks should contain a few zones designed for different purposes. These are the pedestrian zone (dedicated to the movement of people), furnishing zone (includes urban trees and benches) and frontage zone (the front parts of businesses adjacent to sidewalks).

Universal Accessibility: sidewalks should be accessible to all people. As part of this principle, some elements that sidewalks should have are curb ramps allowing for easy movement off and on a sidewalk and tactile surfaces that allow those with sight impairments to distinguish where a sidewalk ends.

Safe Connections: sidewalks are also a place of facilitating other forms of transportation like as public transit. Safe bus stops, traffic lights allowing for plenty of time for pedestrians to cross, raised crossings are all elements making sidewalks safer and more usable.

Clear Signage: maps, tables, traffic lights all guide sidewalk users and provide more information used to navigate their path.

Attractive Spaces: it is important for sidewalks to be inviting to users. This might include elements like tree lining and benches, which entice people to occupy sidewalks more.

Permanent Security: sidewalks should feel like and be safe spaces during all times of the day and night. Street lights and active business fronts can achieve this principle and increase the feeling of safety for sidewalk users.

Quality Surfaces: the material constructing the sidewalk should be uniform and stable. This makes for a comfortable and safe travel space for users.

Efficient Drainage: draining rain water efficiently contributes to sidewalk usability. A technique often used to increase water absorption in the soil surrounding tree lining are, for instance, rain gardens that collect water in a depressed surface from the road and the rest of the sidewalk.

Asymmetrical & Hidden Effects

The lack of good and safe sidewalks does not affect everyone equally. Consider the following examples:

How women travel differently from men:

Studies in women’s travel patterns show that women, unlike men, make more trips but cover shorter-distances. UCLA’s Brian D. Taylor and UC Berkeley’s Michael Mauch have studied the division of household duties and how they affect transportation patterns, finding that women are more likely to conduct grocery and child-care related trips. Importantly, this leads to “trip-chaining”, or the linking a few tasks together in one trip. A lot of these tasks involve non-car transportation which women are more likely to depend on.

It is not hard to see that the choices we make when designing cities, conscious or not, end up having uneven impacts on different groups in out society. Consider how Stockholm, “a highly snow-prone city, typically targeted roads for snow-removal rather than entries to day cares, footpaths, and cycle paths, which are more often used by women and children”. In Frankfurt it “is common for the narrowness of pavements over its river crossings to disadvantage certain pedestrians. In a risky maneuver, caregivers with strollers are forced to momentarily step onto the roadway, which is itself two lanes wide”.

That said, in recent years many cities have been implementing solutions that are more inclusive and aim at understanding these inequalities. “Gendered budgets” involve analyzing and re-proportioning municipal budgets in ways that boost gender equality. In Lyon, this policy has already lead to the increase of well-lit pedestrian paths and stop on demand bus systems. Sweden has also implemented street cleaning practices in which residential streets get cleared first. It will be interesting to see how cities use data analysis techniques to understand their citizen’s needs better and increase safety and enjoyment for all. Check out this video for more information on how Sweden works to achieve sustainable gender equality in urban planning:

(New ways of) doing business:

Street vendors, restaurants and other companies have long used the sidewalk as a place of business. Outdoor dining, advertising, temporary sidewalk sales and pop-ups are all ways businesses utilize the sidewalk space to their benefit. Standing on the sidewalk, you can sip a coffee and eat a croissant while taking in the city sounds or be stopped by sellers wanting to hand out testers for their perfumes. It is a space that can be enjoyable and relaxing, but that can also feel irritating and unwelcoming. How should we consider these dynamics and how should this public space be shared?

Let’s consider emerging technologies like delivery scooters, robots and automated vehicles. Besides delivering you post-hangover meals, these new products are also a prime example of how technology interacts with our daily lives. There has been concern over how adopting tech like delivery robots disproportionately hurt seniors or people with disabilities. And there are numerous examples: in Pittsburgh “a delivery robot blocked the path of a woman in a wheelchair when it didn’t “recognize” the pedestrian coming its way. It left her sitting in the street as the light turned green before she was able to squeeze past the frozen robot onto the sidewalk”. Scooters operating on the sidewalk are also a nuisance: cities such as San Francisco have pushed for scooter companies to adopt “geofencing” which prevents users from riding in certain areas, to relatively low success.

These examples push us to consider the issue of the commercialization of public space more deeply. Now and in the future, we have to think about who the street really belongs to, and who gets to use it. If delivery robots endanger sidewalk users, especially those with disabilities, or if pedestrians have to side-step around discarded scooters, who is actually benefiting from these new technologies on the street? How do we decide which solutions are equitable and how do we think about the problems with our current ones?

Conclusion

All in all, sidewalks have more to them than meets the eye: they are a place of movement, lingering, waiting but also a space of continuous debate on access and priority. How will sidewalks look like in 10 years? 50? 100? How will we use what we already know about their history in the way we design them in the future? How we be able to ensure that accessibility and inclusiveness inspire us to build better sidewalks? Or will sidewalks become the next frontier of powerful people deciding how the street should look and act?

With these considerations, I hope this issue was helpful in someway in informing your own thoughts on sidewalks!